Understanding the vestibular system, behaviour, and how to support children’s sensory needs

Have you ever watched your child spin in circles for minutes on end? Or jump repeatedly on the couch like it’s a trampoline? Maybe they’re the opposite — they avoid swings, get car sick, or hate climbing.

Children are made to move. Whether they’re bouncing on furniture, spinning in circles, or flopping onto the floor in dramatic rolls, it can be equal parts fascinating and frustrating for the adults watching them. But what if there’s more going on than just high energy?

What if these movements are telling us something important about the brain?

Welcome to the world of the vestibular system — the sense that helps children balance, focus, and feel grounded. Once you understand this system, your view of childhood behaviour will change. What once seemed chaotic starts to make perfect, biological sense.

📥 𝘿𝙤𝙬𝙣𝙡𝙤𝙖𝙙 𝙩𝙝𝙚 𝙁𝙍𝙀𝙀 𝙄𝙣𝙛𝙤𝙜𝙧𝙖𝙥𝙝𝙞𝙘

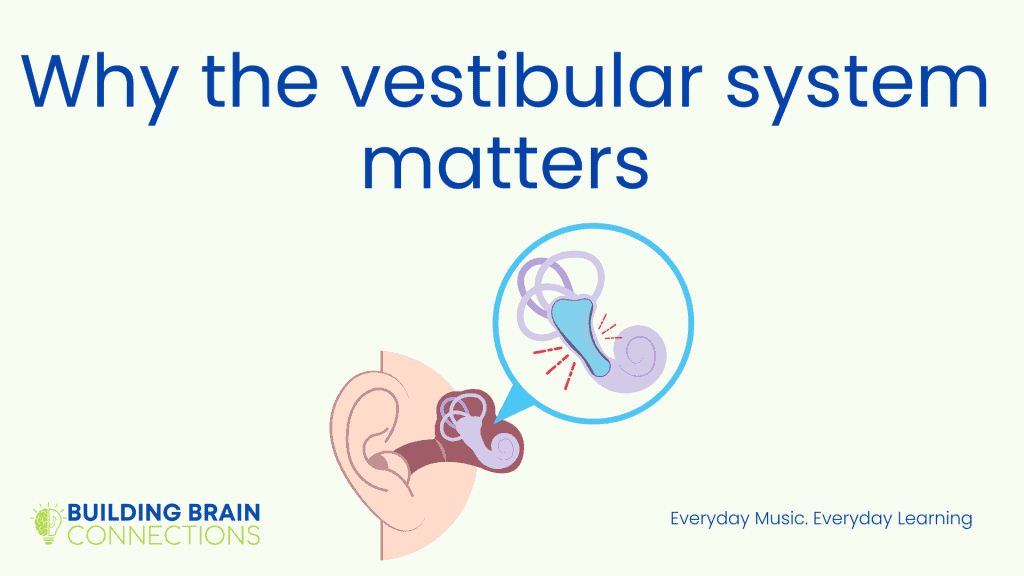

What Is the Vestibular System — And Why Does It Matter?

The vestibular system is part of our inner ear and is responsible for detecting movement, gravity, and spatial orientation. It’s often called the “sixth sense” — not because it’s magical, but because it operates silently in the background, coordinating how we move, stand, focus, and even learn.

It’s like an internal GPS and air traffic controller rolled into one. The vestibular system receives movement data from the body and sends that information to the brain. If everything’s working properly, the brain can organise this data efficiently and focus on higher-level tasks like thinking, reading, and socialising.

But if the vestibular system isn’t operating correctly — if the GPS signal is weak or the controller is confused — the brain becomes overwhelmed. Like trying to hear a train announcement in a loud, chaotic station, it has to work much harder to interpret what’s going on.

The Brain in Overdrive: When Messages Don’t Make Sense

Imagine standing in a crowded train station. The speaker crackles overhead: “Sydney train approaching.” But instead of hearing “Sydney train approach” your brain hears: “Cindy is a cockroach.” Confused, you freeze. Your brain has to work overtime to figure out what’s actually been said.

This is what a child’s brain experiences when their vestibular system is out of sync. Their internal world becomes unpredictable — and they may react with anxiety, hyperactivity, emotional outbursts, or withdrawal.

A well-functioning vestibular system gives children a sense of “I know where I am in space” — and that sense is foundational. It underpins:

- Balance and posture

- Body coordination

- Reading and writing

- Attention and focus

- Emotional self-regulation

As noted in occupational therapy research, when the brain struggles to integrate sensory messages properly, children may respond with unexpected or disorganised behaviours (Bundy et al., 2020). That’s why understanding this sense can be such a game-changer.

What Happens When It’s Out of Sync?

When the vestibular system isn’t doing its job, children often try to compensate — sometimes in ways that look like misbehaviour.

The Movers (Vestibular-Seekers)

Some children crave movement. Their body tells them, “I need more input to regulate.” So they:

- Spin

- Rock

- Jump on furniture

- Hang upside down

- Bounce constantly

- Shake their head or fidget non-stop

This movement isn’t defiance. It’s their body’s brilliant attempt to self-regulate. Think of a tired adult who shakes their head or taps their feet to stay awake in a long meeting — it’s the same idea.

Behaviour is communication. Movement is a message.

Diana F Cameron

Movement stimulates the vestibular system, giving the brain the alertness it craves.

The Still Ones (Vestibular-Avoiders)

Other children are the opposite. They avoid movement because their vestibular system overreacts. These kids might:

- Get carsick easily

- Dislike swings, spinning, or climbing

- Cry when tipped backward in play

- Struggle with stairs or uneven ground

To them, the world can feel unstable — like walking on a rocking boat. Avoidance becomes a way to feel safe. But it also means they may miss out on vital sensory input needed for development.

Either way — constant movement or fear of it — the child’s behaviour is telling a story. And when we learn to listen, we can respond with insight and compassion.

The Secret of Vestibular “Upgrades”

One of the most fascinating things in early development is that the brain seems to prepare for each major motor milestone by engaging in repetitive movement beforehand.

This is what I call a vestibular upgrade.

Here’s what that looks like:

Jumping: A Classic Example

About 6–8 weeks before a toddler learns to jump, you’ll often see a dramatic increase in vestibular-seeking behaviour:

- They spin round and round on the spot

- They roll down hills, beds, or the lounge room floor

- They want to swing constantly

- They grab poles in public places and twirl endlessly

Parents may feel frustrated, but these movements are a sign that the brain is preparing for a new skill. It’s like installing a software upgrade before launching a new app.

Watch closely: the child tries to jump — their heels lift, but their toes stay grounded. That’s because the brain knows they don’t yet have the balance to land safely. Launching isn’t the hard part — landing is.

So the body repeats rolling, spinning, swinging — until the vestibular system strengthens, and the toddler can jump safely. It’s an extraordinary process of self-tuning and calibration.

Understanding this allows us to reframe “annoying” behaviour as developmental brilliance.

The 3 Semicircular Canals — And Why They Matter

Inside the vestibular system are three tiny, fluid-filled tubes called the semicircular canals. Each one detects a different kind of movement:

- Horizontal canal – side-to-side movement (e.g. shaking your head “no”)

- Posterior canal – nodding forward and back (e.g. “yes” motion)

- Anterior canal – rotational or tilting movement (e.g. cartwheels, rolling)

Each canal sends signals to the brain about motion in its plane. When these messages are clear and synchronised, the brain feels safe and steady. But if they’re distorted or underdeveloped, the brain has to work harder to interpret what’s happening.

This is where intentional movement strategies become powerful.

3-Way Rocking: Calming the Brain in Three Dimensions

To support vestibular regulation, I developed a technique called 3-Way Rocking. It gently stimulates each of the semicircular canals using specific movements:

- Side-to-side rocking (stimulates the horizontal canal)

- Forward-and-back rocking (stimulates the posterior canal)

- Circular or diagonal rocking (stimulates the anterior canal)

When used with calming music and rhythm, this kind of movement has a regulating effect on the entire nervous system. I’ve seen it soothe children experiencing night terrors, reduce dysregulation in toddlers, and help children transition into more organised behaviour.

It’s not just movement for movement’s sake — it’s intentional, rhythmic, multi-dimensional sensory input that helps the brain do its job.

Sitting Still Takes the Most Balance of All

Here’s a surprising truth: sitting still is actually the most advanced form of balance the brain can perform.

That’s because dynamic movement (like walking or jumping) is easier for the vestibular system to handle than static control. Being still requires the brain to constantly adjust small muscle groups to keep you upright.

So if your child can’t sit still during story time, or fidgets constantly during lessons, it might not be poor behaviour — it could be their brain struggling to maintain balance.

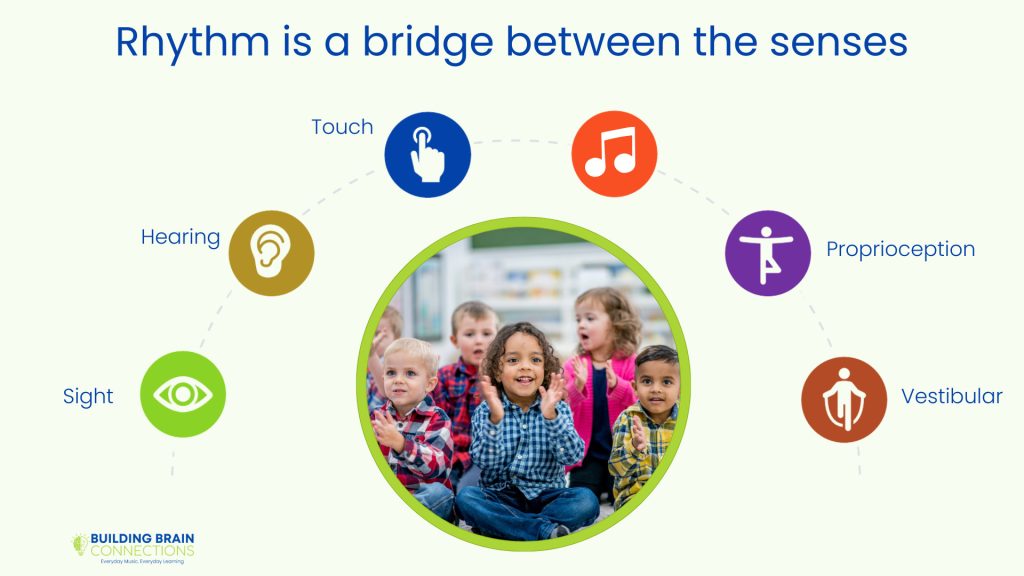

Music and Rhythm: The Hidden Allies

Rhythm is the bridge between the senses.

When you add music to movement — especially steady, predictable beats — you activate a powerful combination of auditory, vestibular, and proprioceptive input. These systems together help children:

- Feel more grounded in their body

- Predict what’s coming next

- Improve their timing, sequencing, and spatial awareness

- Regulate emotion through predictability and pattern

This is why music-based movement classes are so beneficial. It’s also why simply rocking with a child to a steady beat — or doing 3-Way Rocking to music — can have such calming effects.

Studies have shown that rhythm and movement together support not just coordination, but also executive function, language processing, and social engagement (Williams et al., 2021).

A Peer-Reviewed Study Supporting Vestibular Intervention

A 2020 study published in the journal Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience explored how vestibular stimulation influences children’s sensorimotor development. The researchers concluded that:

“Vestibular interventions significantly improved postural control, balance, and attention in children with sensory processing difficulties.”

This confirms what so many parents and educators have observed anecdotally: when the vestibular system is regulated, everything else improves — from focus to confidence to connection.

Final Thoughts: What Is Their Brain Trying to Tell You?

Next time your child spins, jumps, or rocks endlessly, don’t rush to correct or label the behaviour.

Instead, ask:

“What is their brain trying to tell me?”

Every roll down the hill…

Every wiggle on the floor…

Every dizzy spin or desperate bounce…

…might just be the brain’s beautiful way of preparing for something bigger.

When we understand the vestibular system — and support it with intentional movement and rhythm — we set the stage for deeper learning, stronger focus, and calmer, more connected children.

Let’s stop punishing the body for trying to do its job.

Let’s start partnering with it — through everyday music, everyday learning.

Responding With Empathy, Not Frustration

Once we understand how crucial the vestibular system is, we can shift from punishing behaviour to supporting development.

Here are some quick dos and don’ts:

✅ DO:

- Offer intentional movement breaks

- Include spinning, swinging, rolling play

- Use rhythmic music and movement games

- Offer deep pressure hugs or weighted blankets for over-responders

- Try 3-Way Rocking before bedtime or after dysregulation

🚫 DON’T:

- Force children to sit still if they can’t yet

- Dismiss constant motion as “bad behaviour”

- Overload sensitive children with fast, unpredictable motion

References (APA 7 Style)

Alessandrini, M., Micarelli, A., Ricci, G., et al. (2020). Vestibular training effects on balance and attention in children with sensorimotor disorders. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience, 14, Article 22. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnint.2020.00022

Bundy, A. C., Lane, S. J., & Murray, E. A. (2020). Sensory Integration: Theory and Practice (3rd ed.). F.A. Davis.

Williams, K. E., Berthelsen, D., Nicholson, J. M., Walker, S., & Abad, V. (2021). Enhancing self-regulation through music-based movement activities in early childhood. Early Child Development and Care, 191(4), 571–584. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2019.1622535

Recent Posts

🐸 A frog, a log… and a whole sensory counting adventure! ✨ This is no ordinary counting book — it's rhythm, rhyme, sound, and layers of learning! Your child will count from 1 to 10 and back...

A fun and rhyming read-aloud picture book for children who love cats — big, small, silly, or grumpy! This playful story celebrates all kinds of cats through rhythm, rhyme, and imagination....